The Spark: A Seed in the Stacks

Innovation often begins with a single question. For Mammoth Distilling, that question emerged during a routine research session in the Michigan State University (MSU) library: What happened to Michigan’s legendary rye varieties?

While researching whiskey heritage in the MSU library, Ari Sussman, an MSU graduate and a Mammoth Distilling team member, stumbled upon a reference to Rosen Rye, a once-dominant grain developed at Michigan Agricultural College (MAC) in the early 1900s. The variety had all but vanished, but its legacy lingered in old advertisements and forgotten seed catalogs.

This chance encounter sparked a visionary partnership between MSU and Mammoth Distilling that is transforming heritage grains into economic opportunity, scientific advancement, and a new chapter in agritourism. Among those driving this vision is Chad Munger, an MSU graduate who graduated from the MSU College of Arts and Letters and is the founder of Mammoth Distilling. Munger’s passion for heritage grains and Michigan’s agricultural legacy has helped bridge the worlds of academia and industry, deepening the partnership’s roots and reach.

“It all started with a story in the stacks and a call to MSU,” said Munger. “That led to a partnership that’s now reshaping our brand and Michigan’s agricultural future.”

Rosen Rye: A Legacy Reborn

Originally developed by Dr. Frank A. Sprague at Michigan Agricultural College in the early 20th century, Rosen Rye quickly emerged as the primary variety utilized in American rye whiskey production. . To preserve its genetic integrity from cross-pollination, seed stock was grown on South Manitou Island in Lake Michigan, making Michigan a national leader in rye production.https://www.nps.gov/slbe/planyourvisit/southmanitouisland.htm

“Rosen was the premier rye variety in the U.S. before Prohibition,” said Dr. Eric Olson, Associate Professor of Wheat Breeding and Genetics at MSU. “It was the industry standard, like the russet Burbank of potatoes.”

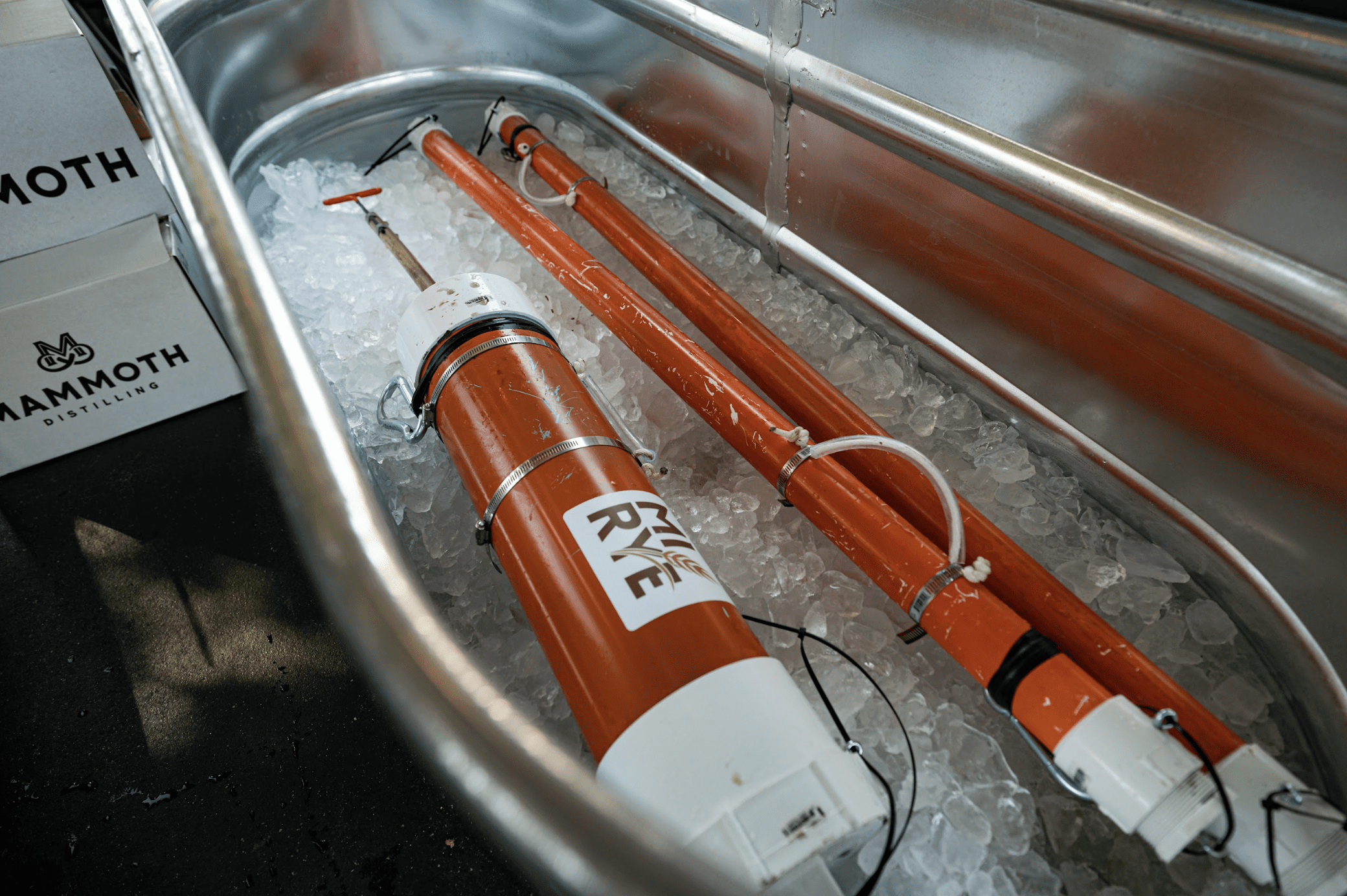

Within weeks of Mammoth’s inquiry, Dr. Olson secured 18 grams of seed from a USDA bank in Idaho. MSU propagated the grain and, utilizing existing connections with the National Park Service, Mammoth was granted permission to restore Rosen Rye cultivation on South Manitou Island, preserving its genetic purity just as it had been a century earlier.

The rediscovery of Rosen Rye was just the beginning of a Michigan Rye revival and a deeper collaboration between MSU and Mammoth, one that would soon expand into a shared vision for economic transformation.

Beyond Rosen Rye

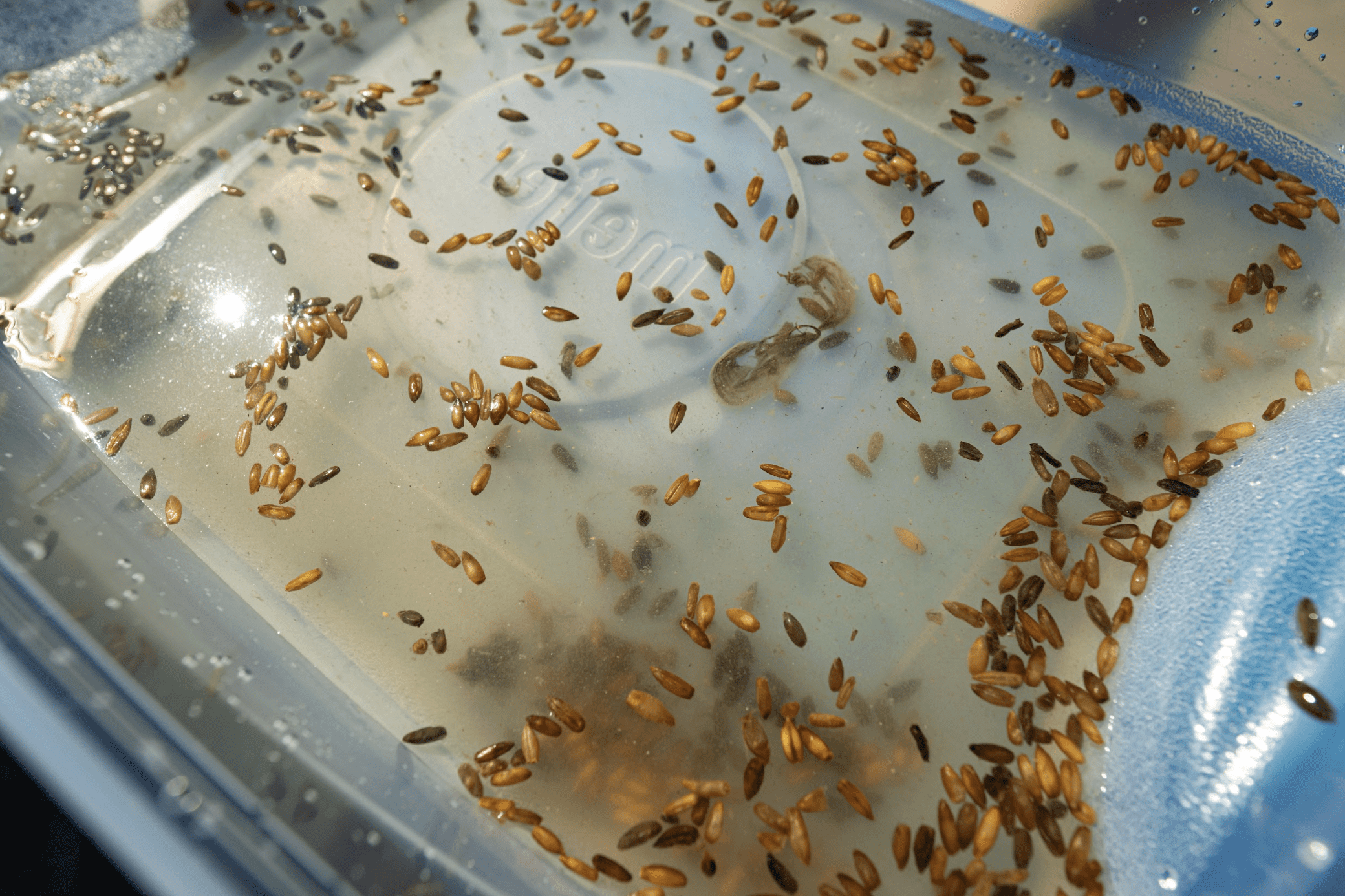

At the heart of this evolution is Bentley Rye, recovered from a 19th-century shipwreck in Lake Huron. In November 1878, the schooner James R. Bentley, carrying 37,000 bushels of rye, sank near 40 Mile Point Lighthouse. For 146 years, this extinct variety, predating Rosen by over three decades, lay preserved in Lake Huron’s cold waters, offering a rare glimpse into pre-industrial rye genetics from an agricultural era of Michigan’s peak rye production period decades before modern mechanized farming practices transformed the landscape.

When divers finally recovered the seeds from the wreck, the moment felt like “winning a million-dollar jackpot,” according to Dr. Olson. Despite attempting three different processes to bring the preserved seeds out of their dormancy, the 146-year-old seeds failed to germinate. But this setback didn’t end the Bentley story; it transformed it into something even more ambitious.

Dr. Olson’s team sequenced DNA from the endosperm and began reconstructing the Bentley genome, comparing it to historical varieties worldwide to trace its origins. “We’re not cloning it, we’re rebuilding it from the genome up,” said Olson. “This is where agro-archaeology meets cutting-edge genomics.”

Building Tomorrow’s Crops Today: MSU’s Hybrid Rye Breeding Program

The process involves identifying chromosome pieces from the historical variety and systematically recreating them using modern breeding techniques.

“We’re creating 12 to 48 individual lines that we can cross-pollinate to recreate that Bentley rye,” Olson explains. “But we’ll have the genetic identity of those lines, so we can reboot it anytime we want.”

The Bentley project represents more than historical recovery; it’s the foundation for MSU to establish the first hybrid rye breeding program at a U.S. public university.

This breakthrough uniquely positions MSU to address a critical agricultural gap—currently, the U.S. imports almost all its rye for whiskey from Germany and Poland. Although rye remains an “orphan crop” that hasn’t received much research attention, Olson sees immense potential: “Rye is far more resilient than wheat. It grows anywhere, under any kind of stress.”

The program embodies MSU’s land-grant mission in action. “Growers look to MSU to know how to do things better,” Olson emphasizes. “We’re here to help them innovate.”

As climate change intensifies pressure on traditional crops, rye’s exceptional resilience positions it as crucial for Michigan’s agricultural future. Through the hybrid breeding program, MSU isn’t just preserving the past; it’s engineering solutions for tomorrow’s challenges while supporting today’s farming communities.

For Michigan farmers, rye offers diversified income, improved soil health, and access to expanding markets. MSU is driving its resurgence through a climate-resilient breeding program tailored to Michigan conditions, with applications spanning spirits, food products, animal feed, and cover crops.

To support this growth, the university is building a comprehensive infrastructure that includes extension services to educate farmers and training programs to prepare the next generation of plant breeders. This integrated approach ensures that the benefits of MSU’s research are effectively transferred from the lab to the field, fostering a sustainable and profitable rye industry.

“We’re doing what MSU has always done—helping farmers grow better crops,” said Olson. “Only now, we’re using genomics, data modeling, and industry partnerships to do it.”

The Partnership: From Field to Flask

The MSU Innovation Center played a pivotal role in turning vision into reality, making connections between key stakeholders and negotiating research agreements.

“The MSU Innovation Center was engaged early on,” said Munger. “They helped us navigate the university and build something truly special.”

The partnership now involves several field trials, master agreements for future research, and ongoing support from the Innovation Center, serving as a model for how universities and companies can collaborate to create value and turn academic expertise into real-world impact.

Jeff Myers, Director of Corporate Partnerships at the MSU Innovation Center’s BusinessConnect Office, collaborated with Munger and Olson to facilitate these partnerships. “Our office greatly appreciates the ongoing collaborative efforts of Chad and Mammoth Distilling,” Myers stated. “MSU works with companies of all sizes from around the world, but it’s especially meaningful when we support the R&D needs of Michigan small businesses,” he added.

Turning Michigan’s Heritage into an Economic Growth Engine

Today, the U.S. imports over $120 million in rye annually, primarily from Europe. “Almost all the rye used in U.S. bourbon comes from Europe,” said Olson. “It’s America’s spirit—but we’re not using American grain.”

With Michigan’s agriculture already contributing $104.7 billion annually to the state economy, replacing rye imports with Michigan-grown grain could generate millions in ripple effects while opening new export markets.

“We’re seeing real demand from distillers and bakers,” said Munger. “And Michigan farmers are perfectly positioned to meet it.”

The Vision: Michigan’s Rye Trail

Mammoth envisions a Michigan Rye Trail—a statewide agritourism initiative inspired by Kentucky’s Bourbon Trail, which generates $9 billion annually and supports over 23,000 jobs. In partnership with MSU, the two are working toward making this vision a reality, combining Mammoth’s entrepreneurial drive with the university’s research, breeding expertise, and infrastructure to elevate rye’s role in Michigan’s agricultural and tourism landscape.

Michigan’s wine region already attracts 1.7 million visitors annually, generating $330 million in expenditures. A Rye Trail could build on this foundation, offering immersive experiences that blend agriculture, history, and hospitality. “We’re not just making whiskey,” said Munger. “We’re building an ecosystem—one that includes growers, distillers, historians, and tourists.”

Looking Ahead

The MSU–Mammoth partnership began with a story in a library and grew into a multi-year collaboration involving faculty, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and community leaders. It demonstrates how academic research, historical preservation, and economic development can converge to create a lasting impact.

“Michigan State checks the box—we have everything to get it done,” said Olson.

The MSU Innovation Center continues to support the partnership while inviting other companies to explore similar collaborations in agriculture, food systems, and beyond.

“Just talk to people,” said Munger. “Every person at MSU leads you to two more. That’s how innovation happens.”

###

Want to Learn More About MSU’s Rye Innovation?

Partner with MSU to Shape the Future of Agriculture and Innovation

The MSU Innovation Center invites companies, growers, and innovators to collaborate on agricultural technologies, heritage grain revival, and rural economic development.

Whether you’re exploring sponsored research, licensing opportunities, or co-developing next-generation solutions, we’re ready to collaborate.

Interested in partnering with MSU faculty on agricultural innovation?

Visit innovationcenter.msu.edu or contact us to start the conversation.