When it comes to farming, becoming more sustainable can also mean becoming more profitable. So it’s only natural that farmers would look to Spartans for help going — and making — green.

Michigan State University researchers have garnered a nearly $2.6 million grant to work with farmers across the country to make their fields more eco-friendly while boosting their farms’ bottom lines. Led by MSU Foundation Professor Bruno Basso, the team is developing conservation practices that cut losses on unproductive plots and make the most out of more fruitful fields.

“This is what we call Precision Conservation,” said Basso, an ecosystems scientist in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station. “It is a big step toward sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems.”

The grant is part of a nationwide initiative called On-Farm Conservation Innovation Trials, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. “On-Farm Trials help producers improve the health of their operations while at the same time helping NRCS build data to show the benefit of innovative conservation systems and practices applied on the land,” said NRCS Acting Chief Kevin Norton.

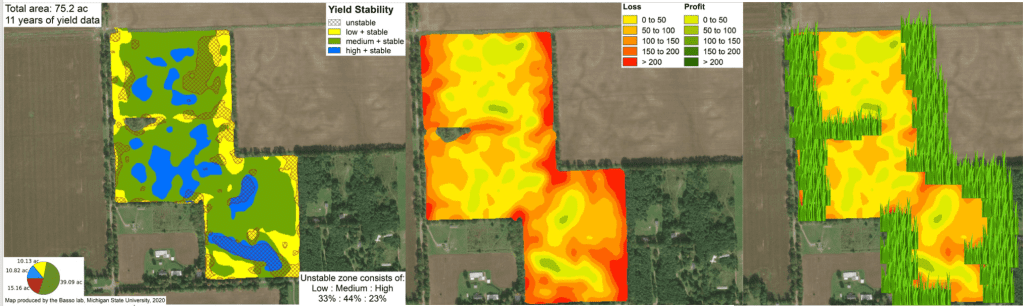

Basso and his team bring expertise in what’s known as digital agriculture to the program. Using images of fields captured by drones, planes and satellites, the researchers create maps of different fields of the same farm. These maps help farmers and researchers develop plans for each location, such as which crops to plant and what management strategies to use.

For this grant project, the team is mapping crop yields and the costs associated with getting those yields. When the researchers identify portions of a field that cost more to maintain than they generate in profit, they’ll work with farmers to convert that land back into natural habitats for native plants, wildlife and pollinators. The team’s project includes an incentive system to help farmers make those changes. Farmers will also recoup time and money spent on keeping up those unprofitable areas.

“Converting unproductive field areas to grassland habitat will support beneficial insects — including natural enemies of crop pests — helping to reduce the need for insecticides,” said Douglas Landis, one of Basso’s collaborators and a University Distinguished Professor in the Department of Entomology.

Also joining the project are University Distinguished Professor Scott Swinton of the Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics and Professor Nick Haddad of the Department of Integrative Biology and the Kellogg Biological Station. By setting aside field areas with the lowest crop yields, precision conservation can sharply cut the hidden cost to farmers of losing crop production, Swinton said.

The Spartan researchers will also be tracking which parts of the farm are making money. They’ll analyze their data to see if farmers can use fertilizers more efficiently to get more bang for their buck. Less fertilizer means lower costs for farmers and less excess making its way into the environment as pollution.

“We can finally achieve greater sustainability,” Basso said. That means “more profit for farmers from higher yields in good parts of the field in addition to incentives to remove unproductive land and applications of agrochemicals that end up in our water resources.”

Basso’s team will be working with farmers in 11 states, including Michigan, to study biodiversity benefits and the overall economics of adopting precision agriculture and precision conservation in different locations. “Farmers are very much on board with this idea and excited to see their hard work on the farm become more efficient,” Basso said.

And don’t just take his word for it.

“This is revolutionary for U.S. agriculture,” said Jeff Sandborn, a farmer in Portland, Michigan, and member of the National Corn Growers Association. Other farmers shared Sandborn’s excitement to collaborate with the MSU team, including Marc Hasenicks of Springport, Michigan, Nathan Smith of Berlin, Illinois, and Brian Sutton, a fifth-generation farmer of Lowell, Indiana.

“By using precision technology in conjunction with aerial imagery, we can achieve great strides for both the farmer and the environment,” Sutton said. “This is truly a win-win.”

This story was first published on MSU Today