University Distinguished Professor devotes career to cause and effect of air pollution.

This summer’s hazy skies caused by the wildfires in Canada prompted air pollution to rise to the center of attention in Michigan and across the nation. Alerts issued by state and federal agencies warning against prolonged outdoor exposure to the lingering smoke gave way to serious public health concerns.

Jack Harkema, University Distinguished Professor in Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, and the Albert C. and Lois E. Dehn Chair in Veterinary Medicine, has devoted his nearly 30-year career at Michigan State University to understanding the health implications of commonly encountered environmental and occupational air pollutants (e.g. ozone and particulate matter) found in both urban and rural communities.

Prior to joining MSU in 1994, Harkema worked nearly a decade at the Inhalation Toxicology Research Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico (now the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute) studying respiratory health effects caused by burning fossil fuels.

Over the years, the board-certified pathologist, veterinarian, and inhalation toxicologist has examined how inhaled air pollutants, including those from wildfire smoke, can exacerbate and even lead to the onset of chronic medical conditions such as asthma, obstructive pulmonary disease, Type 2 diabetes, as well as cardiovascular, metabolic and autoimmune diseases.

Before the Canadian fires in late June, Harkema secured a new $452,500 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to continue research with the University of New Mexico to examine the health effects of metal content and neurotoxicity in wildfire smoke. The researchers applied for funding, in part, because of the wildfires that had previously ravaged the U.S. West Coast. At the time, they had no way of knowing the wildfires in Canada that would eventually cause further alarm close to home.

“I focus on work that is very applied,” said Harkema, director of the Laboratory for Environmental and Toxicologic Pathology at MSU. “Even though we do basic research on laboratory animals (mainly mice) to look at mechanisms of all these pollutants and their potential harm, we’re really interested in what’s going on in the field, and that’s what’s happening in cities, and rural areas around air pollution.”

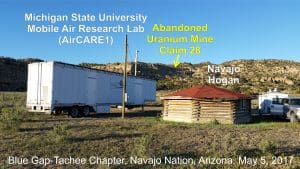

And it’s no exaggeration that Harkema, director of the Mobile Air Research Laboratories operated out of MSU, studies and experiences air pollutants firsthand. In 2009, he led the deployment of a 53-foot, 36,000-pound mobile air research laboratory dubbed “AirCARE 2” throughout southern Michigan, including the rural town of Dexter along with areas near Detroit. The mobile unit equips researchers with the ability to analyze “real world pollution in at-risk communities,” he said.

The $400,000 lab, the second of its kind (the first, AIRCARE 1, was also under the direction of Harkema), selectively pulls small particles from the air and analyzes them for chemical components responsible for damaging health effects. Through these samples, the researchers seek to discover which pollutants are the most harmful and where they come from.

“We recently brought a mobile air lab back from New Mexico on a rural Navaho reservation where we finished a study with Dr. Matthew Campen from the University of New Mexico,” he said. “With new work generated from that, we’re starting collaboration with Dr. Campen and some other researchers here at MSU to look at the wildfires out West and how they have impacted the rest of the country because they generate so much smoke that travels long distances.”

With the recent alarm over the Canadian wildfires this summer, Harkema and his colleagues realize the urgency of air quality findings to inform the public. However, the mobile labs and their operation come with a hefty price tag, he said.

GLACIER

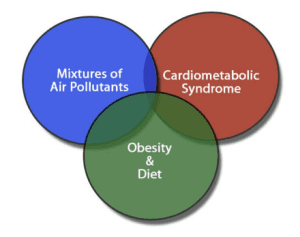

The mobile air labs launched by Harkema and a team of researchers were part of the Great Lakes Air Center for Integrative Environmental Research (GLACIER) administered through MSU. Established in part by funding from the Environmental Protection Agency in 2011, the multidisciplinary center explored the interrelationship between certain facets of the cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) and air pollution – considered by U.S. health officials as one of the most prevalent and important global health and environmental issues.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost all the global population (99%) breathes air that exceeds WHO guideline limits and contains high levels of air pollutants, with low- and middle-income countries suffering the highest exposures. Ambient, or outdoor, air pollution is estimated to have caused 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2019.

In addition to MSU researchers, GLACIER involved biomedical and environmental experts from the University of Michigan, the Ohio State University, and the University of Maryland. It was one of four EPA Clean Air Research Centers, each with a specific focus, established to study air pollutants.

GLACIER scientists were centered on understanding the health effects of air pollutant mixtures, especially for those with chronic cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic conditions. The researchers published more than 50 peer-reviewed papers on the adverse impacts of particulate matter and gaseous air pollutants on metabolic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes in both urban and rural areas.

“Our GLACIER studies provided some of the first preclinical toxicologic findings that environmental exposure to air pollution can not only enhance but also cause the onset of Type 2 diabetes and asthma, using laboratory animal models of human disease,” Harkema said.

The work of GLACIER, which continued for nearly a decade until around 2020, is what Harkema describes as having some of the most influential impacts and outcomes of his career to date. For instance, it helped play a role in his appointment to the nine-member board of the American Thoracic Society’s (ATS) Environmental Health Policy Committee. And in 2018, he became one of just three veterinarians to become the first cohort of ATS Fellows. The vast majority of fellows are doctors of human pulmonary medicine.

ATS is an international society of more than 16,000 members – physicians, research scientists, nurses, and other allied healthcare professionals –with a mission to improve health worldwide by advancing research, clinical care, and public health in respiratory disease, critical illness, and sleep disorders.

Ultimately, Harkema was named chair of the ATS Environmental Health Policy Committee (ATS EHPC) from 2021 through 2023, a position in which he helped serve as a resource for the ATS Government Relations Office and advised the ATS Executive Committee and its Board of Directors on policy and priority issues, among other critical roles.

“I think the work that GLACIER does have some of the most significant outcomes of all,” said Harkema. “It certainly has impacted policy because of my subsequent roles with ATS [as chair and as a board member]. We had to respond right away on issues related to the environment, health and pollution. The ATS EHPC has written abstracts and briefs, some of which went all the way to the Supreme Court. The committee has been very active and influential, especially in the policy arena.”

His TSA work has been praised for its benefits to One Health, a concept combining the importance of research at the intersections of environmental health, human health and animal health. In fact, Harkema’s invited talk at the ATS International Conference this past spring in Washington D.C. focused on climate change, the pathology of air pollution and One Health.

Described by colleague Srinand Sreevatsan, associate dean of Research and Graduate Studies at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine, Harkema’s findings and accomplishments are “a testament to the impact veterinary medicine has on global health.”

Omega-3 fatty acids as intervention

While determining the cause of harmful air pollutants is pivotal, Harkema is also heavily involved in research collaborations to address potential ways to prevent and even treat toxicant-induced flaring of autoimmune diseases such as lupus.

“We’ve concentrated on pollutants like ozone and particulate matter, and the health impacts have been shown to be unquestioned,” he said. “We then started asking, ‘how can we intervene?’ – that was the next part of our mission moving on.”

His work with James Pestka, a University Distinguished Professor of food science and human nutrition at MSU, and Jenifer Fenton, a nutritional biochemist at MSU, has looked at an omega-3 fatty acid called DHA, or docosahexaenoic acid, and its ability to stop a known trigger of lupus. Their research has shown that DHA, found in fatty, cold-water fish such as salmon, can stop the onset of lupus when the disease is caused by a toxic material typically inhaled near construction, agriculture, and mining sites.

Together, the MSU researchers have contributed to preclinical medical studies on mice models that demonstrate the safe dietary interventions of omega-3 fatty acid supplements in preventing and even treating toxicant (e.g., silica dust)-induced flaring of diseases such as lupus.

On the cusp of COVID-19

Harkema has contributed to work around such critically important issues as coronavirus through building a vast network of research collaborators over the years.

Teaming up with researchers from the University of North Carolina, Harkema has been involved in research on the pulmonary pathology of SARS-CoV-1 and -2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus) and vaccine efficacy. SARS-Co-1 was identified in 2003 as a contributing agent to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), characterized by pneumonia symptoms that sometimes results in death. Like SARS-CoV-2, it is a zoonotic virus, meaning it is transmittable from animals to humans.

In 2022, Harkema was contacted by world-renown UNC biomedical doctors Ralph Baric (virologist), Richard Boucher (pulmonary clinician) and Mark Heise (virologist) asking if he would be interested in collaborating with them on NIH-funded preclinical genetic studies using mice models of COVID-19 and screening potential coronavirus vaccines for various variants of SARS-CoV-2.

“UNC is one of the few in the country that can actually do inhalation exposure through intranasal (through the nose) inoculation (of mice),” said Harkema. “So, it’s really all about safety studies of different types of coronavirus vaccines and the impacts they could have on humans. And then, understanding the gene responses and identifying people who are more susceptible to the virus.”

A separate health-related study including Harkema and led by James Wagner, associate professor for the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, revealed that individuals with prediabetes or diabetes living in ozone-polluted areas may have an increased risk for the development of interstitial lung disease, an irreversible fibrotic disease with a high mortality rate.

Published in late 2020 during the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic with researchers from Duke University’s Department of Medicine, the study in diabetic mice was particularly of interest since it suggested that individuals with a common metabolic disease, Type 2 diabetes, who are at risk for severe acute and chronic lung diseases of COVID-19, could also be particularly susceptible to similar pulmonary pathology caused by a commonly encountered gaseous air pollutant – ozone.

In conclusion

When asked what the top three things the public should know about his work, Harkema – whose work is funded in part by MSU AgBioResearch – responded:

- Our laboratory studies have been designed to provide new knowledge that impacts environmental health policy decisions.

- We have contributed to preclinical studies that demonstrate the potentially efficient and safe dietary interventions of omega-3 fatty acid supplements to prevent and even treat toxicant-induced flaring of autoimmune diseases like lupus.

- Our environmental studies have been focused on health effects of subpopulations of people in urban and rural communities particularly susceptible to the adverse effects of air pollutant exposure, e.g., people with type 2 diabetes and asthma.

While most consider air pollution an urban issue, Harkema said studies show that rural areas, especially those with agricultural sectors, are also impacted.

“This is a worldwide issue,” he said. “The work we do has an impact on protecting both human and animal health in urban and rural communities through better air quality standards and guidelines based on sound science.”

This story first appeared on the MSU AgBioResearch website