Few institutions in the world are positioned to address changes in our climate better than leading research universities. They play a critical role in advancing our understanding of climate science and its impacts, training leaders in emerging fields, educating the public and spurring innovation.

In a world that feels unpredictable, Michigan State University is meeting the moment by creating practical climate solutions today that will ensure a more sustainable and secure future.

Across the university, more than 500 faculty are engaged in research that addresses global challenges related to the changing climate and its effects, often working in interdisciplinary teams and in partnership with other universities and communities around the world.

The university’s commitment to making a difference locally and globally is reflected in its position in the 2024 Quacquarelli Symonds Sustainability Ranking, which places it in the top 3% of schools in the world as well as the nation. MSU also ranks highly in the 2023 Times Higher Education Impact rankings that measure how well universities are meeting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

Sustaining our most vital resource: water

There isn’t a state in the nation more influenced, shaped or connected by freshwater than Michigan. From the Great Lakes to 11,000 inland lakes and countless rivers and streams, water provides a drinking source for more than 8 million residents and supports critical industries like agriculture and tourism.

For decades, MSU researchers have played a leading role in safeguarding this vital resource. From coasts to fields, they share their expertise with communities in real time to understand challenges and develop innovative interventions to keep the state’s water, land and people healthy.

“You cannot study and try to solve water problems without understanding the climate signature and its role in these problems,” says Joan Rose, one of the world’s top water experts and Homer Nowlin Chair in Water Research at MSU as well as a recipient of the Stockholm Water Prize.

The university has steadily invested in its water research enterprise over decades, establishing the Institute of Water Research in the 1960s, followed by the Global Water Initiative and most recently, the MSU Water Alliance, a bridging organization that harnesses the university’s vast water research expertise to address immense challenges.

Today, more than 200 water researchers hailing from 13 departments and seven colleges across MSU represent areas ranging from the natural and social sciences to communications to health to engineering and beyond.

“Our researchers see themselves as trying to solve problems at various scales with understanding the climate, the role that climate plays, and with an emphasis on water quality and environmental justice and ethics,” says Rose. “I find it amazing that, collectively, we have this large number of faculty within the water space, and they all have this vision for how they approach their work.”

For some of these water researchers, that work begins on land.

Farming for the future

For nearly 160 years, generations of the Isley family have cultivated the fertile soil of Lenawee County, Michigan, located about 25 miles from the shores of western Lake Erie in the River Raisin Watershed.

Today, Jim and Laurie Isley, with son Jake, operate Sunrise Farms and its 1,100 acres dedicated to corn and soybeans.

The family takes pride in its stewardship of the land and farming operation, implementing no-till and strip-till systems, cover crops, filter strips and water retention structures to keep nutrients on the farm.

The Isleys made natural partners for MSU researcher Ehsan Ghane, associate professor and MSU Extension specialist in the Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering. Ghane and the Isleys are examining the effectiveness of a water management system — controlled drainage — to see how it is best implemented and how effective this system is at keeping nutrients in fields rather than draining into surrounding waterways where they can create harmful algae blooms.

Together with farmers and agricultural stakeholders across Michigan, and supported by partnerships with the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, or MDARD, the Michigan Soybean Committee, the Corn Marketing Program of Michigan and Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, or EGLE, Ghane is exploring practices he hopes will assist Michigan farmers in abiding by what he calls, “the golden rule of drainage: drain only what is necessary for crop production and not a drop more.”

Ghane and his research team recently received a $1.2 million grant extension from MDARD to continue his “Edge-of-Field” research project that began in 2018 on three farms in the River Raisin Watershed, including the Isleys’, which investigated the effectiveness of conservation drainage practices.

“Our research is conducted on privately owned farmland, and we partner closely with the landowners, farmers and producers,” says Ghane. “We share data with them, and they share their farming practices with us, so we both learn from each other. Our partnership with the farmers is a critical component of this research.”

Laurie Isley, who is a farmer director for Michigan on the United Soybean Board, says MSU’s emphasis on practical, on-field research, and allowing Michigan farmers to be part of a solutions-based approach to improving water quality is what drew her family to the project.

MSU collaborates with farmers in the area through the River Raisin Watershed Council, Michigan Farm Bureau, Conservation Districts, MSU Extension and other organizations aimed at reducing environmental impact and water quality issues in the region.

Ultimately, researchers aim to prove that drainage water can decrease the amount of nutrient runoff in fields, and additionally work with Michigan farmers to adapt those techniques to their respective environment and operations. Reducing nutrient loss on fields could also bring economic benefits to farmers in the long run.

“MSU does a great job making the science something farmers can understand and use,” says Laurie Isley. “We know not every farmer can adopt every new technique, but every farmer can do something in the way of conservation, and research like Dr. Ghane’s provides proof that these techniques will be effective.”

Reducing toxic algae blooms

For about two decades, annual algae blooms — fed primarily by phosphorus loss from sources like agricultural fields, animal facilities and wastewater treatment plants, among others — have developed in the western portion of Lake Erie.

In the Western Lake Erie Basin, blooms of blue green algae, called cyanobacteria, can produce toxins that can kill fish, mammals and birds, and can cause human illness.

According to a study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, harmful algal blooms cause approximately $82 million annually in economic losses in fishing and tourism in the Great Lakes region.

Lake Erie has been identified as an impaired watershed, and climate change exacerbates the problem of farm pollution runoff. The Great Lakes region is experiencing more intense and sporadic rain events, leading to periods of drought followed by floods that send polluted water streaming off farm fields and into Lake Erie. Data collection by MSU from the previous five years on partner farms has shown as much as 25% phosphorus loss reduction using these drainage methods compared to control fields. Researchers believe these methods have the potential to capture even more than the initial studies indicate.

“This research allows us to understand the effectiveness of our conservation practices, how we can improve those practices and how we can play our part to reduce the potential negative impact on water quality,” Jake Isley says.

Empowering farmers to lead the way

The drainage techniques Ghane and his team are implementing have proven effective in managing nitrate losses on fields draining into the Mississippi River, says Michigan Farm Bureau Conservation and Regulatory Specialist Laura Campbell. Implementing these techniques in the Western Lake Erie Basin will provide insight into how well the same will hold true for phosphorus losses into Lake Erie.

“Phosphorus management is a crucial step forward for the protection of the Western Lake Erie Basin, and Michigan farmers are invested in making sure they do the best they can to protect water quality in their own watershed,” Campbell says.

Campbell says research of this magnitude and scope requires stakeholder engagement, and MSU plays a key role in collaborating and communicating research processes and findings with farmers, state and federal agencies, commodity advocates and other stakeholders to ensure the information is available and applicable to farms and fields throughout the region and the state.

The Isleys’ son Jake and his wife LeeAnn represent the future of Sunrise Farms, and participating in research like Ghane’s “Edge-of-Field” project provides foundational data to help them continue to adapt and implement practices into their operations that produce environmental benefits.

“If we didn’t have Dr. Ghane’s monitoring station, we could say all these systems make sense and we think these practices will have an impact, but unless we do the testing, we really don’t know. This provides clarity on the practices we’ve started and the system we’re building,” Jake Isley says.

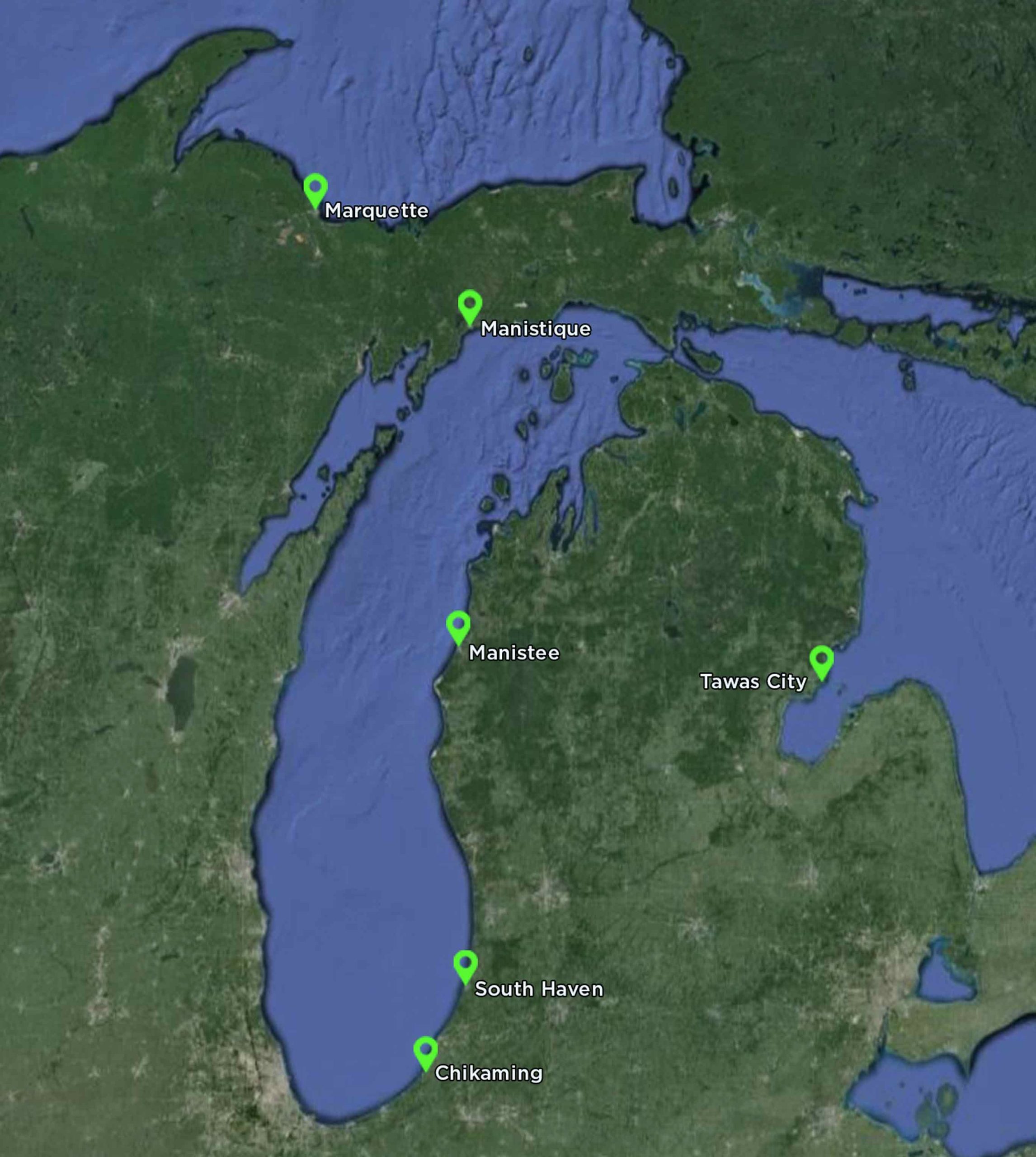

Predicting future coastal health

When Lake Michigan rose to record-high water levels in 2020, storms amplified the breaking waves wearing away the shoreline, exposing tree roots and revealing the foundations of vulnerable homes. David Bunte, supervisor of Chikaming Township in the southwestern corner of Michigan, watched as the protective beaches disappeared faster than nature restored them. For Bunte, this was not only a professional challenge, but a personal one too, as family, friends and neighbors reached out to him for advice.

“We’re dealing with lakefront erosion where sand dunes were worn down and there was a lot of damage to property, and our residents were concerned,” says Bunte. “We needed to mitigate the problems we were having and plan better for the future.”

Bunte wasn’t alone. Communities throughout the Great Lakes wanted solutions to protect their local shorelines. Coastal managers across the state reached out to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy for guidance. Meanwhile, EGLE Water Resource Division’s Michigan Coastal Management Program was searching for more long-term data to help coastal managers make better-informed decisions when managing their local shorelines.

“The Great Lakes are unique,” says Emily Kirkpatrick, the Michigan Coastal Management Program’s coastal hazards coordinator. “We want to understand all the factors involved in coastal erosion and beach recovery, and to be able to communicate that information to the public and local decision makers.”

To fill that data gap, a team from MSU — backed by state and federal grants and some high-flying drones — stepped up.

Championing citizen science

Typically, the Great Lakes have their lowest water levels in the winter and the highest in the summer. These levels are tied to short-term weather patterns and long-term climate variations that can fluctuate depending on the amount of rainfall in a few days or the number of storms in a month.

“Changing lake levels are difficult to predict,” says Ethan Theuerkauf, assistant professor of geography in the College of Social Science at MSU. “The one thing that is really challenging about the Great Lakes is being able to predict what is going to happen five or 10 years in the future.”

Theuerkauf and his team have been studying how Michigan’s coastline is changing, why it is changing and what communities can do about it through its Coastlines and People program, which is creating a model for other such communities worldwide. To assess the erosion along Michigan’s shorelines, Theuerkauf and his team were awarded a National Science Foundation grant to establish a citizen-science program called the Interdisciplinary Citizen-based Coastal Remote Sensing for Adaptive Management, or IC-CREAM, program.

This first-of-its-kind program trained residents in several communities along lakes Michigan and Huron — including Chikaming Township — and in both of Michigan’s peninsulas to capture drone images of coastlines before and after storms. Their efforts help monitor erosion in real time, which contributed to the research in this field.

Residents captured hundreds of images that were stitched together by Theuerkauf and his team, then converted into a digital elevation model to show coastal changes over time.

Working with the state of Michigan through its Coastal Management Program and with the National Park Service through a Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grant, Theuerkauf and his team used publicly available data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Army Corps of Engineers to examine wave and water level conditions.

“We can look at the waves and track the sand that eroded from the shoreline and determine where the sand went and whether it will come back,” says Theuerkauf. “We’ve learned that our coast is really good at pulling sand away, but the waves are not very good at pushing it back.”

This data reinforced that even though the researchers weren’t going to be able to predict record high or low lake levels, they could study where the sand went that was eroding from the coastline.

“With changing lake levels, where along this shore do the waves actually touch the sand and move it around?” asks Theuerkauf. “How often are we getting conditions that move sand back onto the beaches?”

Theuerkauf and his team discovered a “sweet spot” approximately 100 to 300 meters near the shoreline where, if the sand eroded from the coast is deposited there, a small fraction of waves can push the sand back onto the beach. But it takes time.

“There are places where the wave action can naturally deposit sand back onto the shore; It’s taken years but, in some cases, the beaches are coming back,” says Theuerkauf. “This really is the first time that we’ve been able to link how sand is moving the nearshore to whether beaches and dunes can recover.”

Researching in every season

More recently, Theuerkauf has been looking at how ice near the coastline plays a role in coastal erosion with another NSF grant.

“Historically, we’ve thought of ice as being like this great protector of our coasts and that as long as we’ve got it there, we’re good,” says Theuerkauf. “As large mounds of ice build up along the shoreline, they can act like a natural seawall. This protects the beach but can end up scouring the lakebed.”

But every location along Michigan’s coastline is different. Traditionally, hard armoring has been used as an option for preventing erosion along shorelines, which uses seawalls to keep waves from reaching the shoreline, or groins, which are perpendicular structures installed along the shore, to prevent sand from being transported away.

“Hard armoring made things worse in Chikaming Township,” says Bunte. “We instituted a hard armor ban in March of 2021.”

Theurkaulf and his team are exploring whether it has helped the coast.

“Our data showed that it did help,” says Theuerkauf. “Because Chikaming’s beaches are coming back.”

Relationships forged between MSU, EGLE’s Michigan Coastal Management Program and Michigan’s coastal communities put critical technology and data in the hands of researchers and coastal managers working to alter the state’s approach to protecting its shorelines.

Theuerkauf and his team plan to continue their research as they learn more about the factors involved in erosion that can be controlled. The goal is for this research to help more communities and make a difference for shorelines today and tomorrow.

Today and tomorrow are in Joan Rose’s mind, too, as she reflects on the work MSU researchers do to develop climate change solutions that improve quality of life now and for the future.

“We have all this intellectual power in this state,” says Rose. “We’re a good example of riding the waves of change and turning the tide, so to speak, so that you’re coming back towards an economic vitality and wellness for people.”

This story was originally published by MSU Today

The MSU Innovation Center is dedicated to fostering innovation, research commercialization, and entrepreneurial activities from the research and discovery happening across our campus every day. We act as the primary interface for researchers aiming to see their research applied to solving real-world problems and making the world a better place to live. We aim to empower faculty, researchers, and students within our community of scholars by providing them with the knowledge, skills, and opportunities to bring their discoveries to the forefront. Through strategic collaborations with the private sector, we aim to amplify the impact of faculty research and drive economic growth while positively impacting society. We foster mutually beneficial, long-term relationships with the private sector through corporate-sponsored research collaborations, technology licensing discussions, and support for faculty entrepreneurs to support the establishment of startup companies.

Is your company interested in collaborating with MSU researchers on the healthier water? Contact us HERE