The National Institutes of Health has awarded a prestigious grant to a College of Human Medicine professor and a Helen Devos Children’s Hospital physician to study a rare genetic disease and related disorders that until recently were unknown.

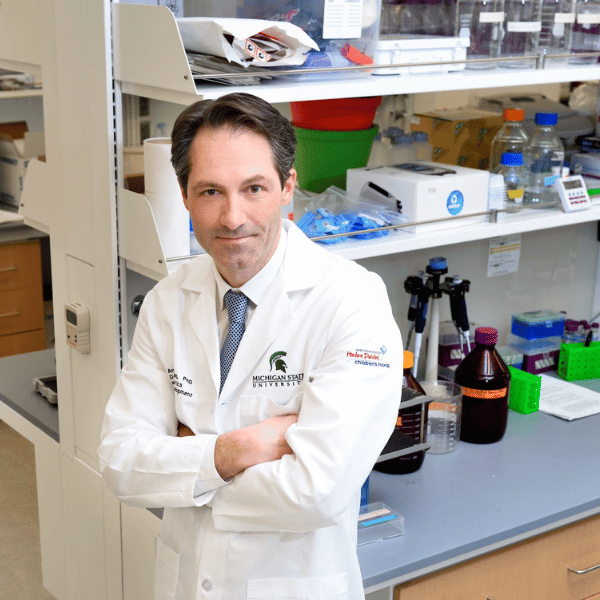

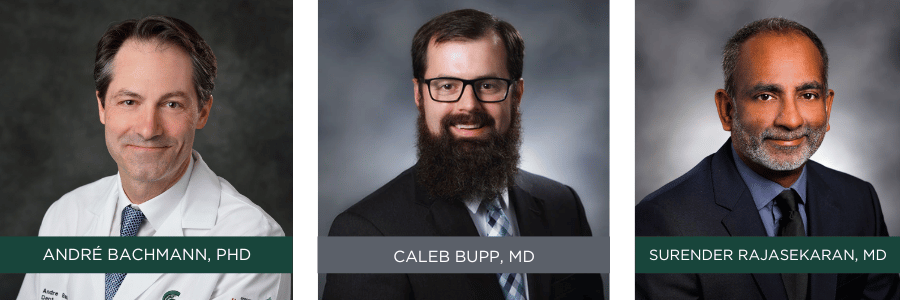

The collaboration between the two scientists – André Bachmann, PhD, a professor of pediatrics, and Caleb Bupp, MD, a medical geneticist at DeVos – grew out of the case of a 3-year-old girl whose symptoms included complete hair loss, an enlarged head, low muscle tone, and developmental delays.

The collaboration between the two scientists – André Bachmann, PhD, a professor of pediatrics, and Caleb Bupp, MD, a medical geneticist at DeVos – grew out of the case of a 3-year-old girl whose symptoms included complete hair loss, an enlarged head, low muscle tone, and developmental delays.

Bupp recalled that he and other physicians “couldn’t figure out what she had,” although a genetic test revealed a mutation in a gene called ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1).

A couple of blocks away in Grand Rapids, Bachmann, associate chair for research in the college’s Department of Pediatrics and Human Development, had spent 30 years studying the ODC1 gene, particularly its role in a childhood cancer called neuroblastoma, which often is fatal.

During a presentation by Bachmann and Surender Rajasekaran, MD, a pediatric intensive care physician at DeVos and assistant professor of pediatrics at MSU, Bupp learned of Bachmann’s research into ODC1, and that when mutated, it can trigger an overproduction of polyamines, a natural compound found in all lifeforms.

“That was the first time I heard this word ‘polyamines,’” Bupp said. That presentation led to a collaboration, the designation of the child’s disorder as Bachmann-Bupp syndrome, and a decision by the NIH to award a $4 million R01 grant for them to further study it and other disorders related to polyamines.

Years earlier, Bachmann had discovered that a drug called difluoromethylornithine, or DFMO, developed in 1978 as an anticancer drug and later used for treating West African sleeping sickness, could be repurposed to treat neuroblastoma.

Years earlier, Bachmann had discovered that a drug called difluoromethylornithine, or DFMO, developed in 1978 as an anticancer drug and later used for treating West African sleeping sickness, could be repurposed to treat neuroblastoma.

In children with neuroblastoma, the overproduction of polyamines in cancer cells causes the cancer to grow.

Polyamines are “important in making cells properly grow,” Bachmann said, but he added: “If you have too much of one polyamine or too little of another, things go awry.” Although Bupp’s patient does not have cancer, the mutation in her ODC1 gene caused her body to accumulate lots of an enzyme called ODC, which triggered a buildup of polyamines in all her cells.

Bachmann’s research showed that DFMO turned down the production of polyamines in neuroblastoma cells. The drug is now in clinical trials as a treatment for neuroblastoma at pediatric hospitals all over the country.

With single-use compassionate authorization by the Food and Drug Administration, Bupp began giving his patient frequent doses of DFMO. The time from discovery of the syndrome to the first dose was less than two years, an unusually quick turnaround. Five years later, the patient, now 7 years old, “has made significant developmental progress,” Bupp said, has gained muscle tone, is able to feed herself, and has grown a full head of hair.

Since the discovery of that first case, he and Bachmann have become aware of 11 other patients worldwide with Bachmann-Bupp syndrome, and they suspect many more are undiagnosed.

The federal grant will allow them to continue studying their eponymous syndrome and other polyamine-related genetic disorders. The grant also will fund a study of a similar genetic disorder called Snyder-Robinson syndrome. That portion of the research will be led by Robert Casero, PhD, a professor of oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Bupp will see patients at DeVos and collect samples for analysis in Bachmann’s lab.

Many questions remain unanswered. What is the proper dose of DFMO? Is there a better drug for treating the syndrome? What other metabolic pathways in the body are affected by the ODC1 mutation? And what other polyamine syndromes are yet to be discovered?

To further their research, Bachmann, Bupp, and Rajasekaran founded the International Center for Polyamine Disorders, a joint venture by MSU and Corewell Health, formerly Spectrum Health. The center is expected to become a worldwide information hub for physicians and parents of patients diagnosed with polyamines disorders.

The partnership between MSU and Corewell Health is essential for medical research to translate into the clinic, Bachmann and Bupp said.

“It’s absolutely key,” Bachmann said. “Nobody these days can do it alone.”

Bupp said: “We have the patients, and MSU doesn’t; MSU has the basic science, and we don’t. I can’t think of a better way to do what we’re doing. This kind of work is the sort of thing that takes a village.”

This story first appeared on the MSU College of Human Medicine website.