This article has been reposted from MSUToday.

Spartan scientists turn to the plant world to understand and treat human illnesses.

It turns out plants and people have more in common than previously thought.

Some of the most renowned plant scientists in the world can be found at Michigan State University, where many are studying how pathogens as well as therapeutic properties found in plants can shed light on the health of humans.

Find out how some of these MSU researchers are putting this knowledge to work, from creating therapies to treating illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease to better understanding similarities between plant and human immune systems.

Developing a treatment for Alzheimer’s using plants

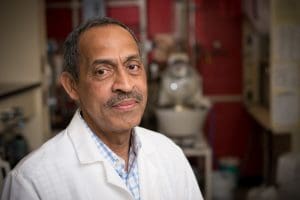

MSU Professor of Horticulture Muraleedharan Nair studies the human health benefits of plants for the treatment of maladies such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, obesity and Type-2 diabetes.

Currently Nair is working with the plant Withania somnifera, commonly known as ashwagandha, on a therapeutic treatment to prevent Alzheimer’s. The fruit of this plant produces an antioxidant compound that he named withanamide. This compound and its analogs have been proven in lab tests and in vitro studies to slow the damage caused by the plaque on brain cells in Alzheimer’s patients.

“When we started looking at the biological activity of the disease, we found that these compounds would allow us to create a therapeutic drug that could prevent and slow down the advancement of the disease,” says Nair. “Once we found withanamide is a powerful antioxidant, we discovered that it can be used directly for human health.”

Nair isolated new anti-inflammatory compounds from the leaves of the plant and withanamide from the fruit. When examining Alzheimer’s mechanisms, he found that the level of oxidative stress on the cells plays a key role in the buildup of plaque that causes destruction of the neuronal cells. Modeling studies led to the conclusion that withanamides can prevent the reaction caused by the plaque.

Nair says he plans to pursue funding and approval of withanamides for clinical trials and eventually bring it into the market for Alzheimer’s patients.

Understanding plant immunity can help people

MSU Foundation Professor Brad Day, in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, is bridging the knowledge gap between the immune systems of plants and humans by better understanding the mechanisms by which plants fend off pathogens.

Two of his current projects, funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, look at the basic mechanisms of how plants regulate their immune systems.

“We have identified several mechanisms in plant immunity that have known functions in human diseases,” he says. “We can use plants as a model to understand how these mechanisms function and how they’ve evolved. In doing that with plants, we can not only understand immunity, but we can also understand mechanisms that reach out into other neurological diseases. For example, a plant can tell us how the mechanism of Alzheimer’s may function. Even though plants don’t have neurosystems, some of those basic underlying chemical mechanisms are shared.”

Studying similarities between what makes plants and humans sick

Research that helps improve crop productivity and resilience could also shine a light on the mechanics of infectious diseases in animals and humans.

Sheng-Yang He is breaking new ground in understanding the importance of a balanced plant microbiome — microorganisms that are tightly associated with a certain plant species or genotype — and the role it plays in regulating plant health. He is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and University Distinguished Professor in plant biology; plant, soil and microbial sciences and microbiology and molecular genetics.

“Without a balanced microbiome, the plant becomes sick in a way that is very reminiscent of diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease in humans,” He says. “IBD is caused by mutations in immune response genes in the human body coupled with something physiological and environmental conditions, like food. In plants, if you affect the immunity response, plus some other environmental factors — such as high humidity — plants will have spontaneous tissue damage, even without pathogen infection, resembling an imbalance of the gut microbiome in humans.”

The processes He studies in plants may be, one day, translated to the development of therapeutics that could treat imbalances in plants and possibly IBD and associated diseases in humans.

Finding ways to better equip plants to manage stress could have a big payoff for people suffering from common illnesses, according to Federica Brandizzi, MSU Foundation Professor of plant biology and 2020 MSU Innovator of the Year.

One of the mechanisms plants use to respond to stress is the unfolded protein response — a signaling pathway activated when a stressor affects the organelle called endoplasmic reticulum. This organelle, which produces one-third of the proteins that make up plants and humans, can make mistakes when stressed.

Brandizzi is using an NIH grant to compare the unfolded protein response in plants to that of humans.

“Because the pathways between mammals and plants are similar, by understanding which genes participate in the unfolded protein response in plants, we can contribute to human health,” she says. “The unfolded protein response in humans is connected with a number of devastating conditions like cancer, Alzheimer’s and diabetes. So, if we can help human health by understanding the processes of plants, we can really make an impact.”

Adapted from stories by Justin Whitmore for Futures Magazine in support of the United Nations’ 2020 Year of Plant Health.