FRIB inaugurates K500 Chip Testing Facility, expanding U.S. microelectronics testing capacity

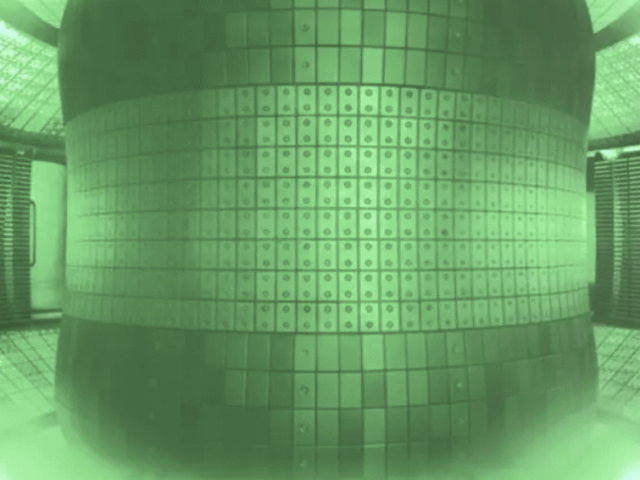

EAST LANSING, Mich. – The Facility for Rare Isotope Beams or FRIB at Michigan State University today marked the inauguration of the K500 Chip Testing Facility or KSEE, expanding U.S. capacity for radiation effects testing of advanced microelectronics used in spaceflight, defense, wireless communications, and autonomous systems. The ribbon cutting recognized the completion and operational launch …